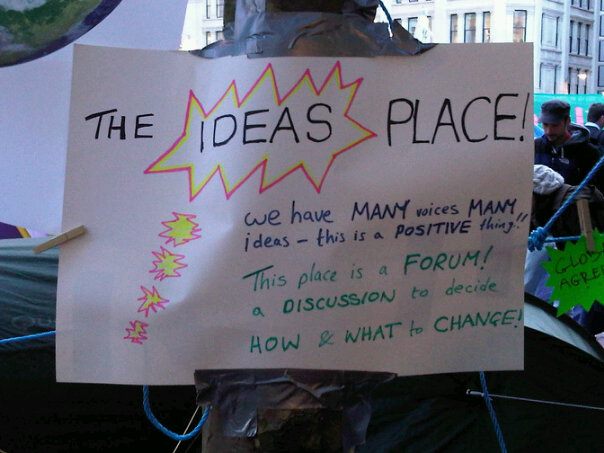

Last Wednesday the Creative Resistance Research Network hosted the first ‘How to Draw Capitalism‘ workshop at Occupy Finsbury Square. Sat in a circle as the sky drew dark and air turned cold, a dozen occupiers huddled around a splattering of markers and pencils. The workshop was designed to explore the ways in which capitalism and capitalists are represented in social movements and develop new ideas for icons and imagery that capture the contemporary moment.

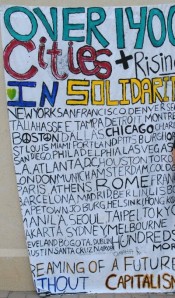

While signs and images decorate Occupy camps across the world, the banners, posters and flattened cardboard canvases covering these reclaimed spaces are far more likely to use words than images. In this movement we have seen an upsurge of witty slogans, bold typefaces and creative ways of displaying the ‘99%,’ but icons and images remain few and far between. As artists’ cooperative JustSeeds founder Josh MacPhee has said, this has much to do with the difficulties of representing global capitalism in simple, iconic imagery. The same goes, it follows, for financial collapse and debt crisis. There are only so many dollar signs one can draw.

In the Civic Paths project, Lana Swartz writes that while the Occupy Movement has not yet created its own sets of icons, as we saw with ACTUP in the 1980s, It does have a visual culture rich with culture jamming. Appropriated popular culture icons range from Monopoly’s Uncle Moneybags to Warner Brothers’ V for Vendetta (an image first appropriated by the web activist group Anonymous). These figures fill the campsites and websites of Occupy protesters. Occupy Sesame Street, Occupy Star Wars and Occupy Gotham have also made a number of appearances, along with Robin Hood in his many variations from Disney to Kevin Costner.

These pop culture plays have received both praise and criticism. Retooling easily recognisable images reaches viewers by appealing to people’s sense of familiarity. We see Cookie Monster hoarding all the cookies and many of us are in on the joke, we can instantly connect to the character and through this, to the sentiment of the symbols. In this sense, popular culture reappropriations are effective for spreading messages as they can reach a wide audience and touch viewers who already have feelings invested in these icons. On the other hand, those critical of culture jamming see these appropriations as further promoting brands, inadvertently drawing attention (and at times money) back to corporate power.

Seeking to create and circulate more new images and icons, Occupy activists in the states have started an interactive, interanational website called OccupyDesign where camps can submit design requests and designers can create and comment on images from these briefs. The organisers also host face-to-face iconathons and their website provides access to stickers, flyers and posters for download and distribution. This initiative taps into David Harvey‘s recent advice that to succeed the Occupy movement must, among other things, “bring together the creative workers and artists whose talents are so often turned into commercial products under the control of big money power.”

As creative jobs, arts education and arts budgets face increasing cuts, now certainly seems the time to tap into existing talent pools of creative workers who have their own stories to tell about life in the crisis. Sat in that circle last Wednesday at Finsbury Square, one of the three underemployed recent graduates of the Royal College of Art participating in the workshop asked the group, “How many people do you know with a permanent contact?” We went around the circle of twenty and thirty-somethings, many with two or more degrees, to each give our answer: “Maybe 10% of my friends”, “I’d say 5”, “I can’t even think of one…”

Anna Feigenbaum

On Sunday Anna Feigenbaum spoke at ‘

On Sunday Anna Feigenbaum spoke at ‘