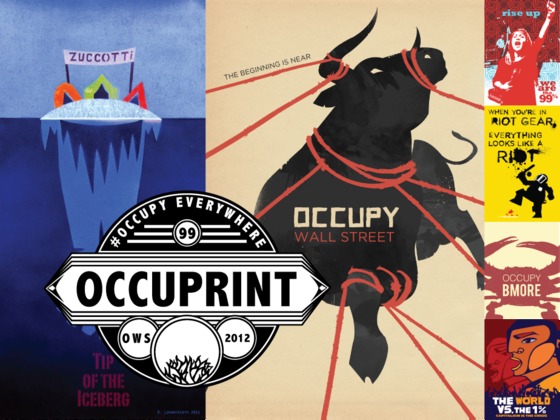

“Someone mentioned to me recently the popular union slogan “8 hours for work, 8 hours for sleep, 8 hours for what we will”. I’ve been thinking over the course of my work with the occupy movement that people are really taking those extra 1-8 hours a day to change the remaining sixteen. In the midst of demanding work, designers tend to forget how powerful those extra hours can be.”

Bubble Wrap Pop-Up

In October 2011 Greta Hansen, Kyung-Jae Kim, Andy Rauchut, and Adam Koogler came together as ‘123 Occupy’ to build strategies for occupation. Their work combines architectural structures, urban design principles and an open source ethos with a commitment to community-building, inspired by the Occupy movement and histories of radical design.

Protestcamps: When and how did you start working together?

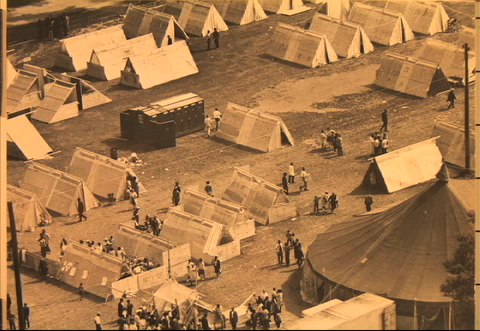

We started working together when the occupation of Zuccotti Park was occupying everyone’s attention. The first thought was “what are they going to do in the winter?” and the second thought was opportunistic. As architects we thought we could try to engage what we already cared about with what was an open ground for ideas. We worked with the Architecture Working Group to brainstorm solutions for the winter, and then we developed a raised insulated water-resistant platform for tents and a collapsible triage station for the medical pavilion. We built them, but unfortunately finished right in time for winter but not in time for the eviction.

Protestcamps: What is your current project and how is it going?

Our current project is also collapsible, an inflatable structure to cover public space and encourage gathering, discussion, etc. We just finished a test model. Our next iteration will double in size to a 30’-0” diameter, and what we learn from that will inform our final inflatable of 60’-0” – 80’-0” in diameter. We call the project Inflatable GA because we think those assemblies, especially the early ones, represented the spirit of the movement. We hope the project will encourage gatherings like those.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYSPcIWhzm0]

Protestcamps: You seem to be coming from different training backgrounds. Could you say a bit about those differences and the collaborative processes you use? How do you see your different skill sets come together in this work?

We’re all architects so our training is not so diverse. I come from an architecture and exhibition design practice, but I’ve been making art projects for the past two years. Andy and Adam work full time in architecture firms and are competent with thinking forms and well as building them. Kyung-Jae also works fulltime in architecture, and he is our graphic side.

Protestcamps: Often in ‘activist circles’ strong lines are drawn between corporate industry work and community/protest work. However, in reality, many designers working in Occupy also work in, or have worked in, the corporate sector. Do you think about these divisions in your practice or working life? Do you see any changes occurring more broadly in the ‘design world’ between, as one recent project in the UK put it, “Creativity, Money and Love“?

All of us are bound to the system somehow. For me, juggling freelance work and art and activist work simultaneously, the boundaries between them can seem less defined. But most of our 4-person group work a daily, strenuous job, like most designers. Someone mentioned to me recently the popular union slogan “8 hours for work, 8 hours for sleep, 8 hours for what we will”. I’ve been thinking over the course my work with the occupy movement that people are really taking those extra 1-8 hours a day to change the remaining sixteen. In the midst of demanding work, designers tend to forget how powerful those extra hours can be. So instead of feeling guilty about time spent in corporate offices, we can remember that it’s our right to balance that work with an effort to change the system we work in.

One of the design firms we look up to for their balance of activism and corporate/government work to is Interboro Partners in Brooklyn. Their project for the Young Architecture Pavilion at PS1 in 2010 was a good example. All the pieces of their design for the museum’s courtyard were pre-designed to become useful pieces of the neighborhood and community after the summer’s run of events and parties.

Protestcamps: One thing I was drawn to in your projects is the way they engage with a kind of ‘open source’ or ‘crowd source’ model for product development. In a traditional product market, you’d take private designs, pitch it to for-profit investors for a stake, and then have your product produced and sold on the market with a price mark up. For 123 Occupy, your designs are made public, your investors are crowdsourced and your product is gifted to the movement. Is this a conscious part of your work? Are you guided by other open source practices and initiatives?

We started because of the completely open source and crowd sourced occupy movement. So everything we are doing is an attempt to connect with that model, and the way for us was through DIY culture. Mimi Zeiger wrote a 4-part series of articles for Design Observer called the Interventionist’s Toolkit. The fourth one included our projects in a discussion of urban activism.

Zeiger’s first article introduces the emergence of these spontaneous urban architecture projects, which have the goal of changing the city through small actions. I’m glad that 123 exists in the realm of these kind of projects. You don’t need a client to make a project and by not having one you create your own agency.

Protestcamps: Your work reminds me of some of Forays‘ projects which were done as everyday street interventions, but could be used in protest settings. This kind of work points, for me, to broader questions of appropriation or applied use. Generally, folks talk of capitalism/corporations ‘appropriating’ art and social movement practices. Yet, in your work and in groups like Forays, appropriation does not seem to work in only one direction. Materials, energy, design principles, landscape, etc. are all put to creative use. How does your group think about these borrowings or re-uses?

cocoon by Forays (Adam Bobbette and Geraldine Juarez)

The main thing I think we are doing is borrowing space and trying to open it up to new uses. Forays’ guerrilla architecture seems to consistently involve the re-use of materials. This is a way to be efficient but also a way to resist our dependence on the consumption of materials, a way to remind us of the resources we are already sitting on. Right now 123 is using a lot of new plastic. So we’re trying to design a smart outlet for that material if and when the inflatables become un-reusable.

Protestcamps: What does 123 Occupy recommend for those interested in radical design? Are there other people, projects, books that you have particularly drawn inspiration from?A direct source of inspiration for us was Michael Rakowitz’s parasite project. He created a series of blow-up pods for the homeless that borrowed warm air from the exhaust vents of buildings. This so-smart way of redirecting air to make comfortable spaces – making something out of waste, invisible waste – is the kind of the epitome of the spontaneous urban design move that you and I both are trying to find.

We’ve also been working alongside Mitch McEwen who runs a small nonprofit called Superfront, which takes advantage of unused and available spaces in New York, Detroit, and LA and turns them into events and design collaborations.

Some of the vintage examples that continue to inspire us, especially for inflatables, come from the radical architecture groups Ant Farm and Archigram.

Michael Rakowitz’s ParaSite Project

Learn how you can build 123 Occupy’s projects.

Follow @protestcamps and subscribe to protestcamps.org for news and reviews of protest camps from around the world.

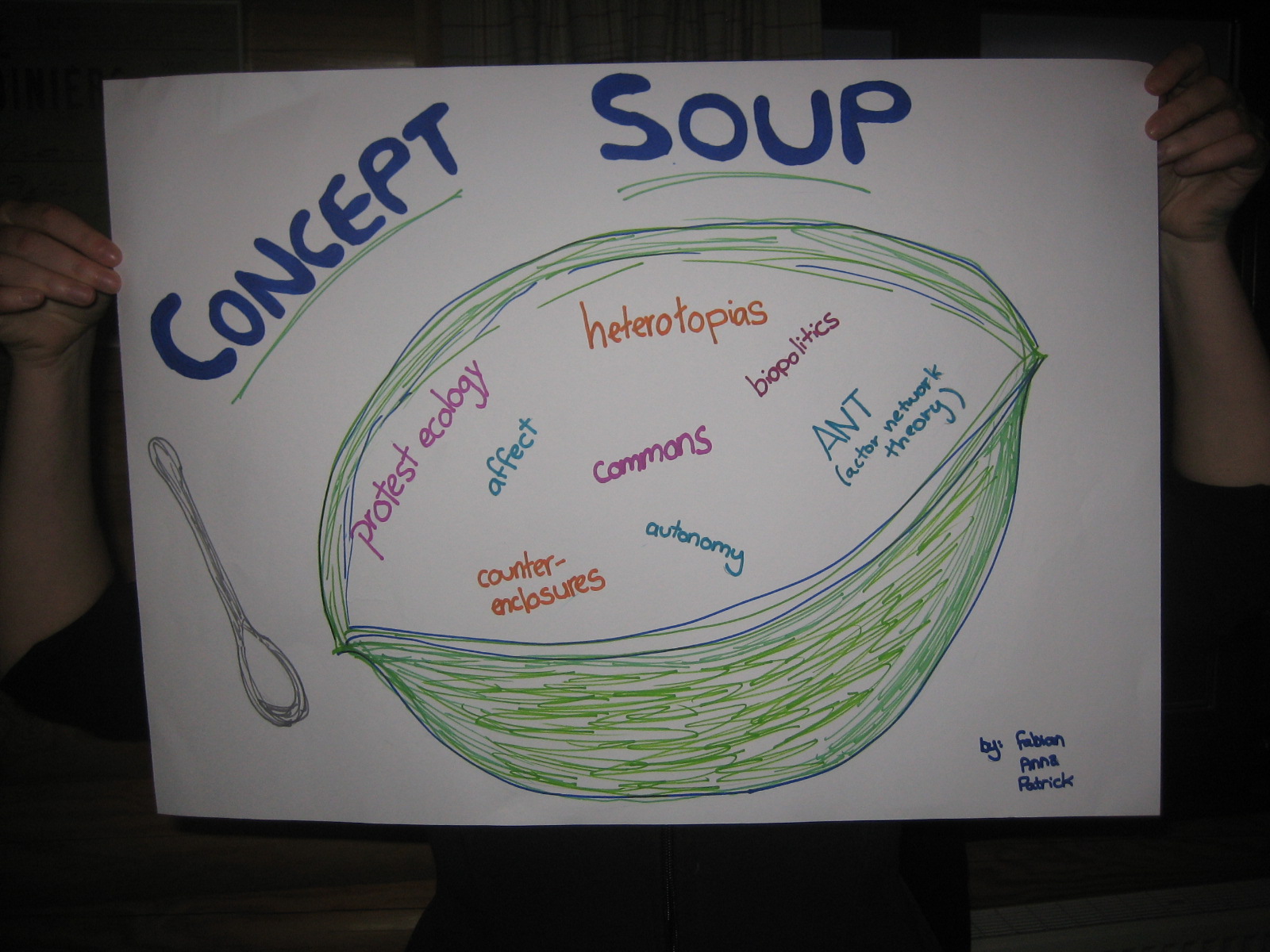

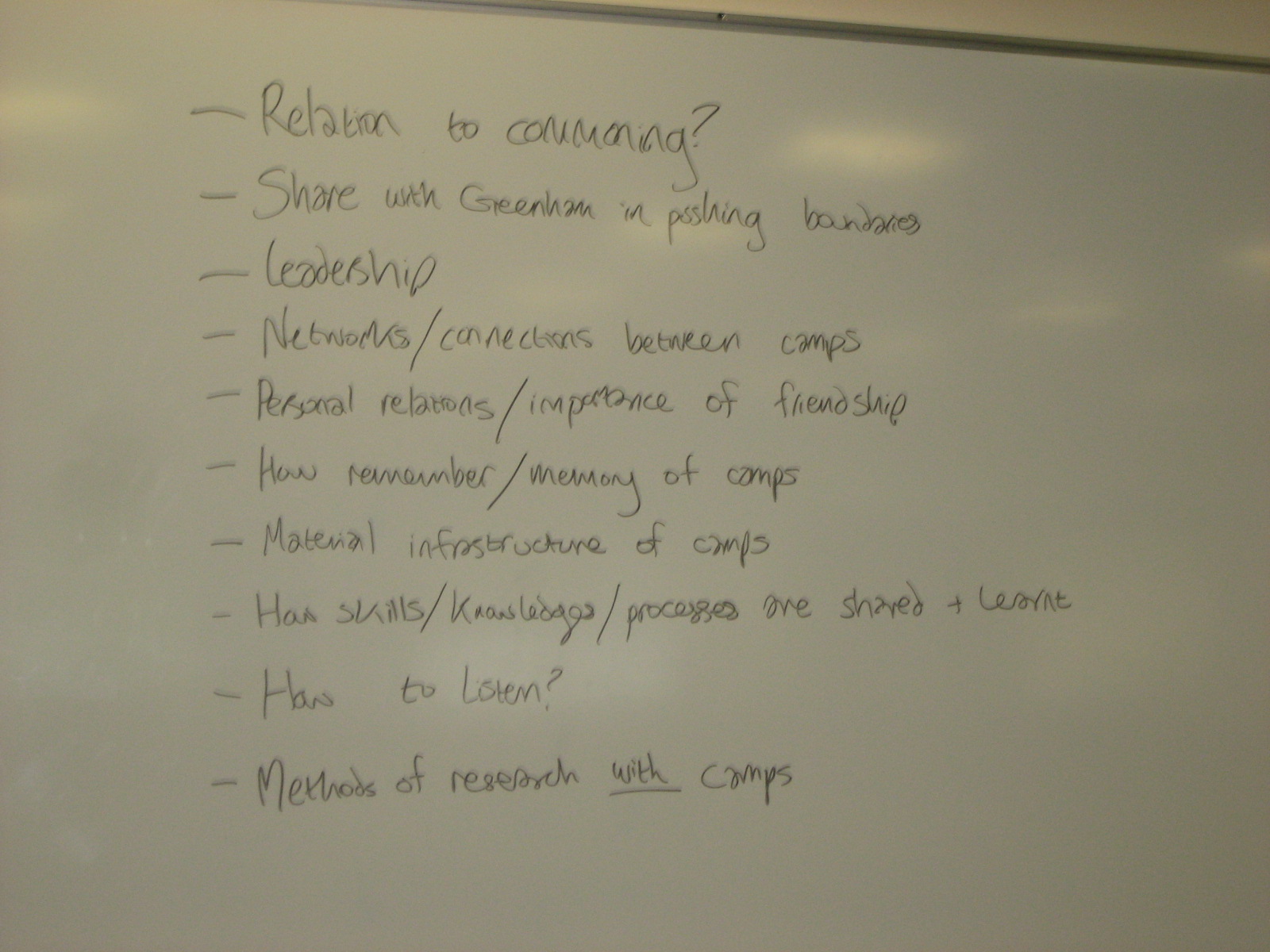

Beginning early on a Saturday morning, the circle got progressively larger as new people started trickling in towards noon. The meeting included people of different ages, backgrounds, and activist or academic experience. Some were activists who had participated in Occupations in Britain and elsewhere and who are researching Occupy-related issues. There were also some Occupy activists interested in what research could offer to the movement.

Beginning early on a Saturday morning, the circle got progressively larger as new people started trickling in towards noon. The meeting included people of different ages, backgrounds, and activist or academic experience. Some were activists who had participated in Occupations in Britain and elsewhere and who are researching Occupy-related issues. There were also some Occupy activists interested in what research could offer to the movement. After a general introduction of the collective and the rules of the discussion (going through the hand signals seems obligatory in every Occupy-related meeting), we used an open methodology to propose topics for the breakaway sessions after lunch. These topics included research ethics, the neoliberal university and its implications for publishing and research, memory and archiving, teaching and learning, as well as doing research for social change.

After a general introduction of the collective and the rules of the discussion (going through the hand signals seems obligatory in every Occupy-related meeting), we used an open methodology to propose topics for the breakaway sessions after lunch. These topics included research ethics, the neoliberal university and its implications for publishing and research, memory and archiving, teaching and learning, as well as doing research for social change.