Protest camps collaborator Anja Kanngieser was recently invited to give a talk at UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design + Townsend Humanities Lab. In her presentation she explored the atmospheres of camps and assemblies with relation to communication and listening, in order to invite consideration on some of the more invisible, sonic geographies of protest camp gatherings

I want to orient our exploration around this slogan because what’s interesting here, besides the witty double reference, is this notion of atmosphere that might be found during these kinds of events, events that are social and political expressions of a coming together in what Gary Genosko (2002) has referred to as a ‘flash of common praxis’, events like demonstrations, occupations and general assemblies predicated on antagonism, hope and invention. I want to look at the speaking of atmospheres, both in terms of the particular assemblages of spaces, infrastructures and sounds, and in terms of the voices that resonate to contribute to the feeling of a moment. Specifically here I make reference to the 2011 Occupy movement and its use of the human microphone, and the general assemblies that took place in Madrid in 2011. While the idea of voice is most usually associated with the capacity to participate in a representative democracy, I’m interested in how this participation is articulated in the sonic aspects of the voice, that is to say the accents, cadences, volumes, pitches, silences, that communicate as much as the words uttered do. Considering the soundings of the voice lets us do two things, firstly it helps us to amplify the non-human aspect, which is often drowned out by the human, by looking at the assemblages and ecologies that make up contentious spaces, and secondly it helps to be more sensitive to the differential voices we might hear, which invites us to explore who participates and how.

The notion of an atmosphere or ambiance is difficult to define in any fixed way, for as Ben Anderson (2009) illustrates ‘as a term in everyday speech, atmosphere traverses distinctions between peoples, things, and spaces. It is possible to talk of: a morning atmosphere, the atmosphere of a room before a meeting, the atmosphere of a city, an atmosphere between two or more people, the atmosphere of a street, the atmosphere of an epoch, an atmosphere in a place of worship, and the atmosphere that surrounds a person, amongst much else. Perhaps there is nothing that doesn’t have an atmosphere or could be described as atmospheric. On the one hand, atmospheres are real phenomena. They ‘envelop’ and thus press on a society ‘from all sides’ with a certain force. On the other, they are not necessarily sensible phenomena.’ For Anderson, given this difficulty of definition we might consider atmospheres as ‘spatially discharged affective qualities that are autonomous from the bodies that they emerge from, enable and perish with’.

For my purposes I want to focus on the connection of such spatially discharged affective qualities to sound and thus to the register of the sensorial (on a side note I will use these terms a little loosely for the purposes of this talk although they do not necessarily mean the same thing as a recent conference in London on ambiances and atmospheres in translation teased out). If an ambiance is a ‘space-time qualified from a sensory point of view’ as Jean-Paul Thibaud (2011) puts it, that is to say how a space is sensed, and how it feels, sound is a prevalent component. Sound surrounds us in all directions – we are immersed in sound on a pathic level. This is to do with the resonant frequency of sound, which means the vibratory quality of sound making it something that is felt through bodies on registers that go beyond that which is audible. In his work on sound and urbanity, Thibaud speaks of resonance as critical to sensing our environment – being entangled in our subjectivation. He writes ‘with the idea of resonance, the world of sound makes explicit the very power of ambiance. It helps to describe the very process by which I feel and sense the world’ (ibid). In this manner, sound was also crucial for Lefebvre’s conceptualisation of rhythmanalysis in mapping the rhythms and ambiances of place and space.

A fundamental expression of sound, especially in spaces of contentious politics, is the voice – and by voice here I refer to the sonic aspects of the voice, how the voice sounds and moves through the air. In his work on voice and language Eduardo Abrantes (2012) argues that voices ‘define territories, in conversation, in public transportation, in the, sometimes awkward, transitions between private and public space’. Furthermore, and this is a point to which I will shortly return ‘they resonate identity, they are biographical sound happenings and can turn every listener into a bearer of this shared individuality’ (ibid).

How we hear and feel sound, including of course the voice, is contingent on its relations to the material and virtual architectures of space. According to Brandon Labelle (2010) ‘sound sets into relief the properties of a given space, its materiality and characteristics, through reverberation and reflection, and, in turn, these characteristics affect the given sound and how it is heard. There is a complexity to this that overrides simple acoustics and filters into a psychology of the imagination’. LaBelle’s comment illustrates the intertwining of the spatial and the relational, at the same time as it indicates the role of the imaginary. The voice, its inflections and resonances, both fills space and is filled by the spaces into which it is projected, to set into motion worlds that encompass physical, psychic, emotional and affective geographies.

The kinds of atmospheres of contentious praxis we are considering require a closer exploration of the interactions between architecture, sound and social practice. Here it is useful to address what Barry Blesser and Ruth Salter (2007) refer to as aural architectures: the ‘composite of numerous surfaces, objects and geometries’ of a given environment. Sounds require space and air for their form, which means they take shape on different scales of space just as they do different temporal scales. This is how spaces manifest sound, even if the sound energy does not originate from the space itself; this occurs through reverberation and reflection – spaces, through their material densities and gaps, modulate and refract sounds and voices in peculiar ways. This occurs too on the level of bodies, the bodily cavity being an anatomical acoustic chamber through which the sound of the voice is shaped.

The physical spaces in which social and cultural politics become organized and collective in certain modes, the places of meetings, effect what kinds of voices are heard and how, just as the space-time of meetings change the nature of place. From community centres to squatted social centres, from university classrooms to public squares, roads to living rooms, from an outdoor camp or a union office to a Skype conference, the spaces in which political conversation and the performative praxes of political organization occur vary in dimension, architecture and temporality. It is imperative to recognize the reciprocitous dynamics of voices and the spaces in which they become, and make, present, because, in the words of Jean-Luc Nancy, ‘the sonorous present is the result of space-time: it spreads through space, or rather it opens a space that is its own, the very spreading out of its resonance, its expansion and its reverberation’ (2007).

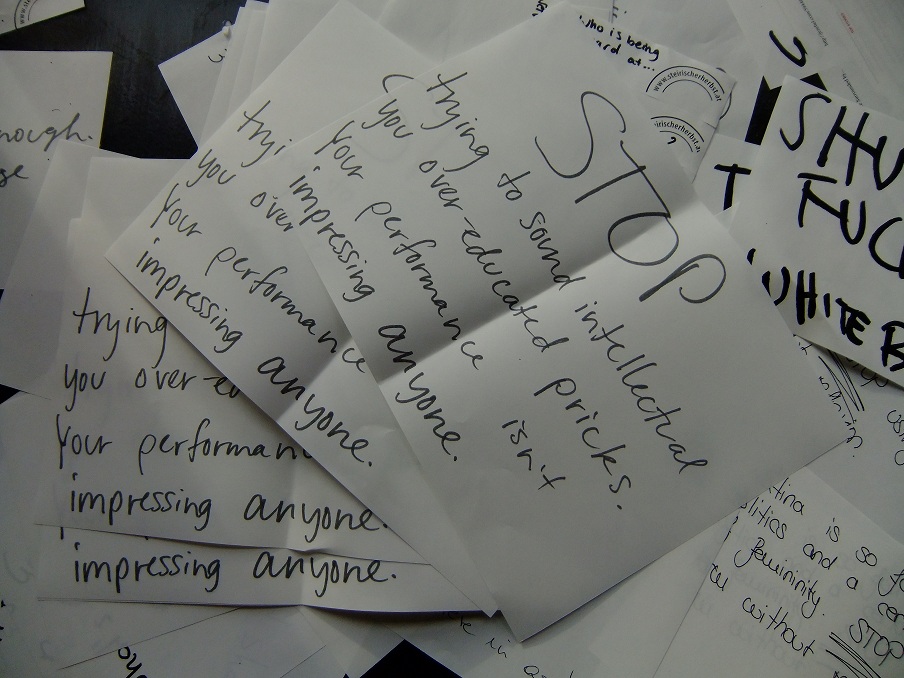

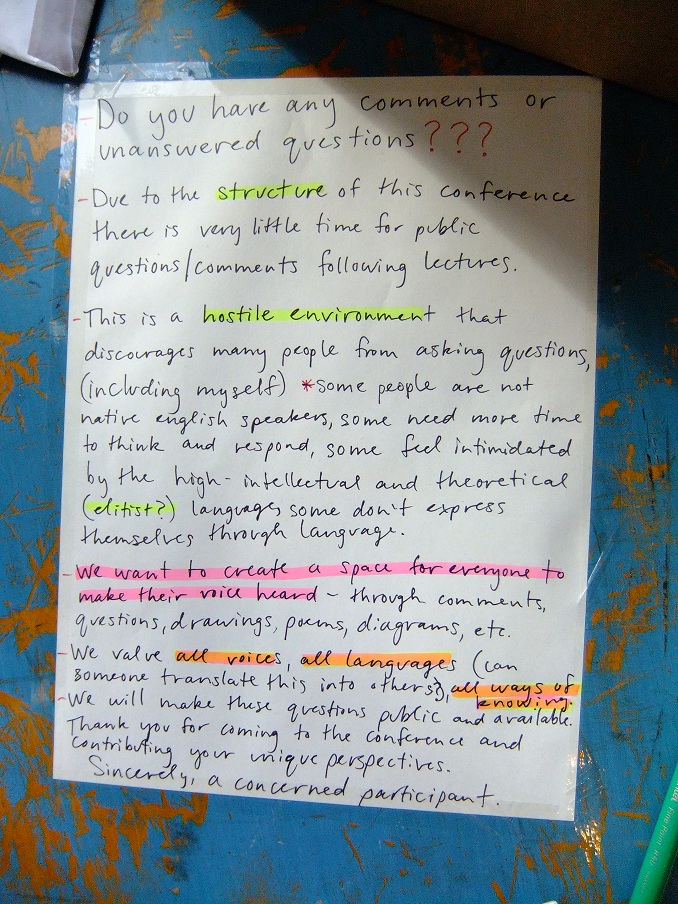

The same can be said for voices. The places in which organization occurs effects participation through differential inclusion, both in terms of a desire to be present and in terms of accessibility. Indeed a space or place may act as a ‘dispositif’ for the production of specific kinds of vocal utterances. This is why, as David Matless proposes, ‘sonic geographical understanding alerts us to the contested values, the precarious balances…which make up place’ (2005). The material and virtual geographies of these sites are steeped in narratives of power; the ways that people engage with, or participate within, spaces hinge on the associations they ascribe to them, the affects and psychic-emotional experiences they have, or project they may have, within them. Such experiences are informed by relations of class, of education, of socio-cultural affiliation, for instance, and may play out in desires for engagement or disengagement. How these atmospheres and spaces are experienced varies with the different emotions and percepts of the individual and the collective, but it is clear that architectures may have particular design elements conducive to producing specific states.

Along with these codings of a particular site, architectural features, or lack thereof, impact upon the disposition and ambiance of an event through spatial acoustic qualities. As Blesser and Salter note, ‘auditory spatial awareness…influences our social behaviour. Some spaces emphasise aural privacy or aggravate loneliness; others reinforce social cohesion’ (2007). The size of a room or space and its volumic capacity, its resonant cavities, its density, its formal or informal feel and function, the arrangement of furniture or objects, all contribute to how the voice moves within it, the kinds of utterances that are likely to be made and the ways in which we listen and respond to one another.

How we listen and respond is also necessarily underpinned by the actions, technologies, desires and intentionalities that coalesce a particular atmosphere. Sound is the result of action and movement, as Thibaud notes with regard to ambiance: ‘it is not only the social activity itself that can be heard but the manner and the conditions in which an action is accomplished. This is why ‘sound is a very useful medium that can help us document the social expression of an ambiance’. The use of sound to explore the geographies and ambiances of contentious politics invites us to consider the methods and techniques of voicing. The human microphone, used during Occupy to extend and amplify voices of speakers when electronic amplification was banned by police, provides one point of illustration.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VoJBZxOh4bY]

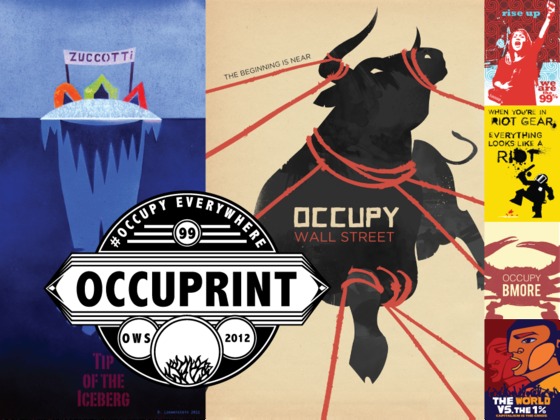

The voice in this sense travels where the body cannot, the voice through these processes of amplification, these communicational and sonic waves extend the reach of expression, resonating within the spaces of Zucotti Park and Wall Street, environments of course marked by long histories of capital accumulation and elitism. The technology of the human microphone, combined with an ethos of openness and commons, put into resonance voices that are atypical for those spaces, unfolding through the voice and through the vocal praxis, as much as through what is said, a counter-power that challenges the hegemonic inhabitation of the space.

Significant too are the voices that permeate and co-create such ambiances, the voices that are heard and those that remain silent, that trace out forces of differential inclusion based on intersectional reproductions of racial, gendered, classed, and abled expressions and mannerisms. For one participant of occupy, the human microphone articulated the assemblages of desire and ideology supportive of open communication.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/88870642″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

We might though also be mindful of how the communicative chains of such technologies can be invisibly iterative of vocal-acoustic territorialities that inscribe delineations of congruity or incongruity (which is especially apparent in comments made by participants about the conflictive voices, the voices that yell out mic check to no response, the disruptions). As Abrantes has argued with respect to such territories and vocal individuation, much can be read in the way the voice interacts with the other ‘voices present, according to its rhythm, its articulation of speed, the spaces it creates for the participation of others, and the spaces that it chooses to fill when inscribing its own participation’ (2012). When the acoustics of voice make tangible the meaning of the situation, interruptions and interferences trouble the perceived synchronicity of the voice and what it is expressing in relation to all other voices (and again, I am referring to the sonic, not linguistic aspects of voice).

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/88871624″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The implications of the voice in the ambiances of contentious politics cannot be overstated, and this is something I have spoken extensively about in my research on voice and organization: how the sonic qualities of the voice affect our capacities to listen and respond to one another. The convergences of vocal tones, accents, cadences, with emotions, desires, affects, techniques and practices of organization, ideologies, architectures, technologies, infrastructures and mechanisms of state repression (including the use of specific sonic warfare), social, cultural, economic landscapes assemble sound environments that are complex and highly mutable. An interesting conjunction to mention here is the role that listening played during the general assemblies in Madrid in 2011, which arose during the occupation of the Puerta del Sol following the arrest of 24 demonstrators during a national day of action against the banking bailouts and the cutback of social programs. In a climate of austerity and the fragmentation of work and welfare, the ways of listening during general assemblies revealed the creation of other ways of being and relating, antagonistic of, and alternative to, those being experienced.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/88871944″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

In these atmospheres and environments of contentious politics the multiplicity of voices mix together in an affective tonality that specifies an ambiance. Addressing these ambiances we can ask how they might feel, how they are populated and what they transduce. To think through affective atmospheres is also to think through processes of subjectivation, which lie at the heart of contentious politics, as Anderson affirms ‘affective atmospheres are a class of experience that occur before and alongside the formation of subjectivity, across human and non-human materialities, and in-between subject/object distinctions. As such, atmospheres are the shared ground from which subjective states and their attendant feelings and emotions emerge’ (2009). They create ‘a space of intensity that overflows a represented world organized into subjects and objects or subjects and other subjects’ (ibid). As such atmospheres generate interference in the representationalism and the easy classification that is being contested in the experimental and novel articulations of contentious politics I am interested in. This is further ameliorated by the changeable nature of their constituencies and their compositions. These are not static environments but mobile and temperamental ones, as defined as much by what is heard and felt as what is not.

By ‘emphasizing the temporal, active and collective dimensions of sound’ as Thibaud stresses we are able ‘to study and to document the unfolding of an atmosphere’ (2011). Attention to the soundings of atmosphere, and I would argue, the voicings of atmosphere, can contribute to a practice of observing that is nuanced and sensitive in its reading. This is a useful perspective to take if, as I raised in the introduction we wish to engage the non-human elements that contribute to these atmospheres, and also if we hope to be more attuned to the differential voices we might hear. And this, I would propose, is particularly relevant in the atmospheres of contentious politics, where as was indicated by the final voice we heard, what is being invented are other ways of making worlds.

The final day for most of the collective was spent with

The final day for most of the collective was spent with

This blog post is written, over the sixth and seventh days of

This blog post is written, over the sixth and seventh days of