Protest Camp’s Anna Feigenbaum discusses No Dash for Gas‘ West Burton power station protest camp in the broader context of direct action and Climate Justice.

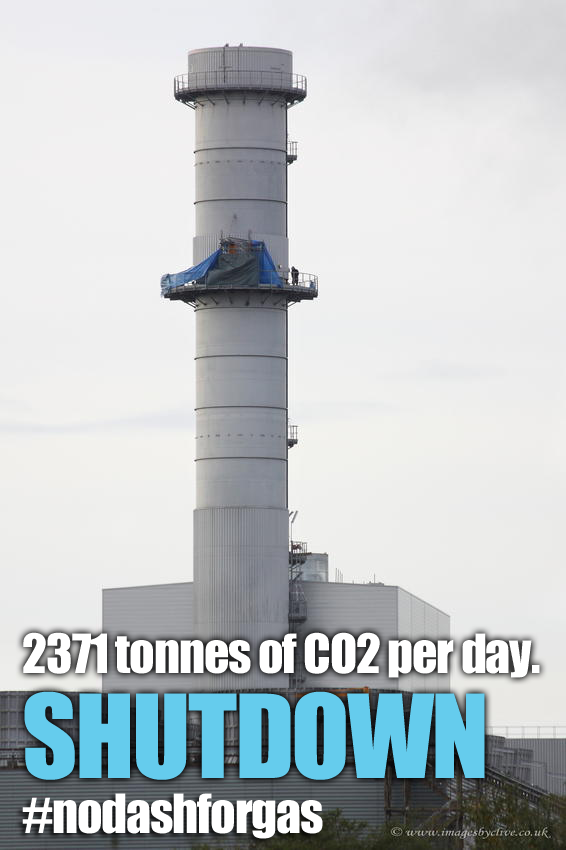

As Hurricane Sandy swept up the Eastern seaboard of North America, after wreaking havoc on Cuba and the Caribbean Islands, across the Atlantic sixteen people crept up the chimneys of a power station to protest polluting fossil fuels. Wrapped in warm clothing and with supplies to last a week, protesters took to these chimney tops, 80 meters above the ground. Every day of their occupation prevents 2,371 tonnes of CO2 from being emitted, the amount an average home would use in 182 years.

As Hurricane Sandy swept up the Eastern seaboard of North America, after wreaking havoc on Cuba and the Caribbean Islands, across the Atlantic sixteen people crept up the chimneys of a power station to protest polluting fossil fuels. Wrapped in warm clothing and with supplies to last a week, protesters took to these chimney tops, 80 meters above the ground. Every day of their occupation prevents 2,371 tonnes of CO2 from being emitted, the amount an average home would use in 182 years.

The target of their action, West Burton power station in England, is a project of big 6 energy firm EDF. This corporation’s track record includes a 1.5€ million fine for spying on Greenpeace, engaging in a secret lobbying campaign regarding subsidies for the disposal costs of waste from their reactors, and covering up flaws in reactor design that could lead to a Chernobyl like disaster. Just last week EDF announced a 10.8% rise in energy prices for its customers, affecting three million households with this hefty hike in a time of austerity.

Despite the rise in ‘superstorms’ like Sandy, in our culture climate change is still seen with scepticism. Clean energy initiatives continue to be treated as corporate charity gestures, rather than as the innovations necessary for the future of our planet. In this climate, direct action is what it takes.

The disappointment of COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, at which delegates from developing nations walked out in disgust; saw the 2050 goal of reducing global CO2 emissions by 80% dropped from agreements. But as PRWatch guest blogger Alex Carlin pointed out, “While the general world opinion of COP15 is that it was a failure, there is the caveat, recognized by many, that a world-wide grassroots movement was galvanized there.”

As part of this global grassroots movement, No Dash for Gas clearly states:

“This action is in defence of the global commons, which are under sustained attack by polluting fossil fuel companies. We are here to challenge corporate power and the rush to further ingrain an energy system that puts short term profits of the few, above the collective needs of the many.”

The targeted West Burton power plant is only one of up to 20 new gas-fired power stations the British Government has planned. Joss Garman, political director of Greenpeace, told the Guardian: “Green-lighting a whole fleet of new fossil fuel power stations would cause a huge jump in emissions.” Climate Justice campaigners, like Garman, want to know why public resources—and taxes—are not being redirected into sustainable energy initiatives.

No Dash for Gas isn’t the first time in recent history that a direct action campaign has climbed its way to climate justice. While ‘Climate Change Activism’ may be a 21st century term, just a decade before the millennium, thousands in the UK protested a pollution heavy, gas-guzzling scheme to extend the roads network.

photo by: Adrian Arbib

In the mid-1990s protest camps swept through the UK targeting the building of new motorways. The first of these ‘anti-roads’ camps appeared in Twyford Down in 1992, and soon after protest campers, with training from professional climbers, were scaling up treetops in Newbury, Solisbury Hill, and at the Pollock ‘Free State’ blockade in Glasgow. The rapid growth of these anti-roads camps led to widespread media coverage, increasing public support and eventually a number of abandoned plans. As the Economist reported in February 1994, “Protesting about new roads has become that rarest of British phenomena, a truly populist movement drawing supporters from all walks of life”

The power of direct action is its ability to intervene at the very site of the problem. For those who can afford the time, and risk the bodily vulnerability of chimney scaling and abseiling, direct action can be, in the words of John Jordan “a radical poetic gesture by which we can achieve meaningful change, both personal and social.” This is the joy of resistance that Emily James’ recent film captures, urging those who can take direct action against Climate Change to ‘Just Do It.’

Combined with the dedication of those engaged in on-going (closer to the ground) campaigning efforts like the work of Friends of the Earth and Platform, direct action amplifies the call to immediately attend to these pressing issues.

In the past few years the UK and Ireland has seen a vast array of protest against corporate culprits of climate change. From 2006 to 2010 ‘Climate Camps’ were organised all around the UK targeting major corporate profiteers of carbon emission from BAA’s Heathrow airport expansion to the European Climate Exchange in London. These camps spread around the world, with direct action sites organised in Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Italy, to name only a few.

In Ireland, the Shell to Sea campaign remains active against Shell’s destruction of the Kilcommon community in their profit-driven pursuit of Oil. Fuel Poverty campaigners have occupied the offices of EDF and British Gas in London, while No Fracking activists and The UK Tar Sands Network draw attention to huge fossil fuel initiatives set on further climate destruction.

Meanwhile, UK groups Climate Rush, Liberate Tate, Rising Tide and BP or not BP target energy oligarchs like BP and Shell. These groups have used soliloquies, flash mobs, pop songs, die-ins , oil spills and even ‘the gift’ of a 16.5 metre wind turbine blade delivered to the lobby of Tate Modern a few months ago in protest of their on-going sponsorship by BP.

These acts of creative resistance leave an impression on our imaginations. They generate news stories across the mainstream media, as videos and memes spread through social media platforms. While ‘all press’ isn’t always ‘good press,’ as the old adage goes, with direct action, all press gets people talking. In a culture where Corporate PR firms want to be the only ones allowed to talk, direct action takes back the power of speech; it is counter-power that can be seen as what Kevin Moloney, and colleagues at Bournemouth University, have recently termed the ‘PR of Dissent.’

Crucially, direct actions like ‘No Dash for Gas’ perform the very connections that need to be made. They draw the links between corporate profit and fuel poverty; between sustainable technologies and sustainable economies; between our need to defend the global commons and the collective resistance it requires.

As No Dash for Gas makes clear, “This is the new battleground for our energy future.”