In this guest blog, Maxine Newlands situates the recent arson attack against Camp Florentine into a broader history of protest camps as vulnerable spaces, from Greenham to ZAD.

Protest camps remain one of the strongest forms of activism in the world, and one of the most vulnerable forms of protest.

Over the past few weeks and months activists have celebrated the anniversary of Occupy, and twenty-years since the Twyford Down camp (1991-1992). We’ve also witnessed resurgence in protest camps as a political strategy, with camps and blockades emerging against airport expansion and mega-dams. The ZAD Occupation against airport expansion, at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, (near Nantes, France) has faced eviction, regrouped and doubled in size. The world’s oldest tribe, Penan, continue to blockade that construction of Sarawak’s (Malaysia) largest hydro-electric dam. And the ‘twenty years since Twyford’ anniversary was a platform to launch a new campaign that highlights the vast road building plans of the coalition.[i]As former Dongas and activists’ both old and new donned sashes listing proposed new road building sites, the celebration of protest camps was marred with conflict, when an Australian protest camp was destroyed in an arson attack. The communal meeting area, kitchen, information point, camp vehicle and rear storage areas were all reduced to cinders[ii].

Camp Florentine or Camp Floz as it is affectionately known lies deep in the heart of the Tasmanian forest. The camp is a two-hour drive from Tasmania’s capital, Hobart. The camp is surrounded by the world heritage site The Florentine valley, home to some of the world’s oldest eucalyptus trees, and habitat of the depleting Tasmanian devil. The devil’s numbers are diminishing from a cancer-like illness and logging of its territory.

Still Wild Still Threatened collective established the camp almost six years ago in the Upper Florentine valley[iii]. Although the valley is surrounded by world heritage site status, the Upper Florentine remains unprotected from logging companies. Along with the Styx, Weld, Arve, Picton and Wedge valleys, they are all harvestable ground for the timber industry. The camp blockades a logging route into the valley as activists gather evidence on the impact of logging practices on the Tasmanian devil’s home.

The latest arson attack is the third such assault on Camp Florentine. In 2008, two activists, locked-on to an old car were brutally attacked by suspected pro-logging campaigners. The assault, filmed by a third activist[iv], shows ‘a sledgehammer-wielding man assaulting a disabled blockade car, with two protesters caught inside, before others kicked in its windows’(Darby, 2008) [v]. The footage was viewed globally and over the following weeks ‘the event and the broader environmental issue of logging in Tasmania continued to feature in broadcast and online news and newspapers’ (Lester[vi], 2010:131).

One of the two protesters involved in the attack, Miranda Gibson, is currently Australia’s longest-running tree-sitting activists. Gibson is living 200 foot above the valley floor, under the canopy of an old growth Eucalyptus tree. From her platform, Miranda blogs at Observertree.org[vii], charting the continued logging activity, Tasmanian devil sightings; and as a media spokesperson for Camp Florentine’s grassroots organisation ‘Still Wild Still Threatened’(SWST).

Then leader of the Australian Greens, Bob Brown hinted the attacks were linked to pro-logging contractors. Brown said the attack was ‘a return to the violent lawlessness of logging vigilantes two decades ago…This pro-logger vigilante attack held the people camped nearby in terror. Like the gelignite bombing of two cars in the East Picton forest in 1991, and the loggers’ violent attack on protestors at Farmhouse Creek in 1986’.

Tasmanian Detective Constable Craig Fry believes this latest attack was misguided revenge for earlier vandalism on logging firm Les Walkden Enterprises. Fry said the incidents ‘do not appear to be linked to any kind of protest activity’, when arsonists caused $700,000(Aus) worth of damage to mechanical logging equipment.

The Camp Florentine attack highlights the vulnerability of protest camps, and their precarious status at the hands of external forces. Despite over forty years of global protest camps, from Greenham Common Peace Camp to Camp Floz, camps remain vulnerable to attack, and acts of repression. Blockade protest camps are often isolated from society, both geographically and metaphorically. Like Camp Florentine and Greenham, isolation increases any vulnerability.

All Women Count activists, Sian Evans who campaigned at both Greenham and OccupyLSX camp notes:

You did feel it was very dangerous, [at Greenham] and here [Occupylsx] was different. At least you’re not out in the middle of the countryside in the same way…where we were living, I was in a bender, at Orange gate, right up-against the fence and the squaddies were going around at night with sharpened metal stakes, and sticking them in [the benders]. We had to call the press, and we did an interview, and that was our protection.

Another Greenham and CND campaigner, Barbara Tizzard, experienced a particularly nasty attack.

A group of international peace people came over and set up a camp …after a while there was the most terrible row and a group of men rushed into the camp saying we’re going to get these peace people…I could hear them slashing tents, you know, knives. When they came to mine, luckily they just pulled it up and slashed across – they didn’t either see me or they didn’t think there was anyone in there, but then the next guy who was a Dutch bloke left his tent unzipped and they just kicked his face in, it was, you know he was really badly damaged…very quickly the police arrived, somebody, of course there weren’t mobiles, somebody outside must have phoned them. (interview with CND and Greenham Common activist Barbara Tizzard)

Whereas Sian notes, ‘the Occupy camp was different because you were in the city, but on the other hand, it’s also when you’ve got a mixed camp [gender], a mixed environment, you know you have to work things out, you have to tackle if there is sexism or any of that together’. Whether isolated or in the heart of the city, protest camps are vulnerable because of their openness. That’s not to say they shouldn’t be open, but it places them into a precarious position.

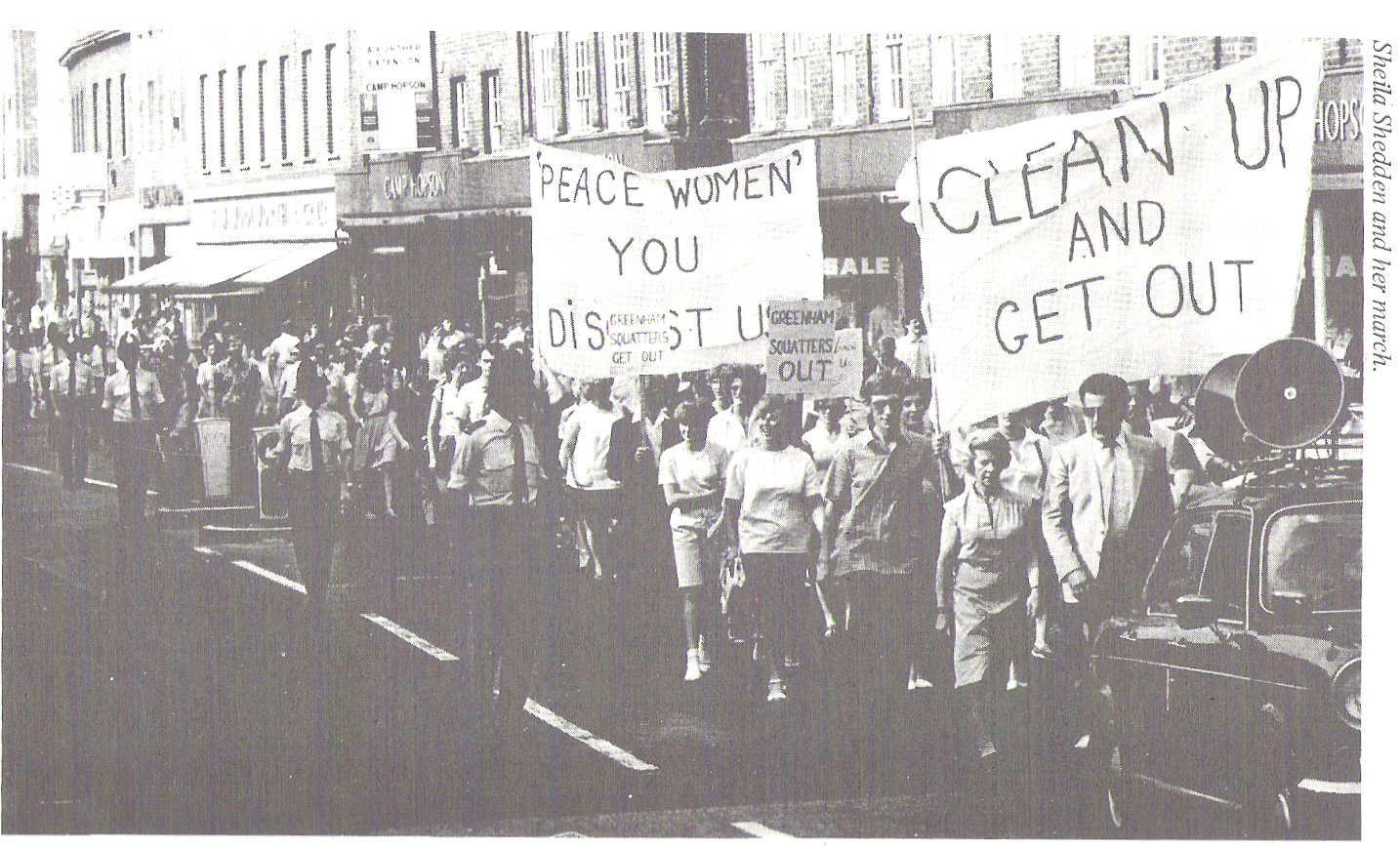

The ‘open’ nature of protest camps can be understood in Foucauldian terms as ‘always presupposes a system of opening and closing that both isolates [it] and makes [it] penetrable’ (Foucault[viii], 1986: 26). Szerszynski[ix] notes that activism is a ‘cultural politics which operates not simply by marking and performing the boundary of its own form of life. It does so in such a way that beckons those outside its boundary, hailing them with a moral claim that one should be on the inside’ (1999: 212). Whereas, Howarth (2006[x]) observes that ‘whilst the inside can be constituted through excluding or demonizing the outside (an enemy to be demonised or a state of anarchy to be feared) the outside is not necessarily another whose otherness threatens to subvert or overflow from the inside’ (119). Howarth is right in his observations that the outside can come from threats to subvert through physical attacks. The Greenham Common peace women were physically demonised by the ‘squaddies’ and even more so by the group ‘Rate-payers Against Greenham Encampments’ (RAGE). As Sian notes ‘They used to put around posters attacking, you know, leaflets with … cartoons depicting a witch … You know there were the dirty lesbians posters.’

Threats can also subvert from the inside through acts of state repression. As Ruth at OccupyLSX camp notes, ‘I think it was vulnerable, and we know all around the world police are actively bringing people to the camps that they thought would make trouble for us. You know, so that vulnerability was actually increased’.

Police tactics to expose the vulnerability of camps by subverting them, is no more prevalent than the example of undercover police officer, Mark Kennedy (Stone). Kenney’s seven year surveillance highlights how protest camps are ‘open’ to acts of repression by the state. PC Kennedy, an officer in the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU) was one of several ‘secret police’ units that observed and infiltrated the activist movements from the 1990s to 2010. Political policing of protest and protest camps began with the formation of the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS,1968), a special branch unit also known as ‘hairies’ [xi]. SDS was formed in reaction to the anti-Vietnam protests, the growth in membership with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), the Cold War and burgeoning Civil Rights Movement ‘all meant an increasing recognition by police of the need for better intelligence, equipment and training for public order work. They now had to find methods of policing mass protest movements in the face of organised attempts to undermine good public order’ (Friends of the Metropolitan Police )[xii]

Between 1994 and 2000, a number of parliamentary measures gave greater powers to the police to conduct surveillance exercises on the activist movement. The National Extremism Tactical Co-ordinator Unit (NECTU[xiii]) (2004), the National Domestic Extremism Team (2005) and the Counter Terrorism Command[xiv] (2006) had powers to monitor and prevent any protest in order to ‘gather intelligence so appropriate policing could take place’ (Hattenstone, 2011[xv]). Other notable undercover police work includes, PC Peter Black who infiltrated the M11 extension protest, Wandsworth, East London (1993); PC Jim Boyling, under the pseudonym, Jim Sutton infiltrated the Reclaim the Streets; PC Lyn Watson would later infiltrate the same group of people as part of the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army (CIRCA); and PC Mark Jacobs who attached himself to the global justice movement, the G8 summit (2005) and later G20 protest camps (2009).

Activists were not surprised that Kennedy had been amongst the collective for a seven-year period: ‘we assume at every meeting there are at least one journalist and one special branch officer’ (Anon, 12:42). Kennedy’s action was subversive and left those who had relationships with him emotionally damaged.

From political policing to physical attacks, protest camps are exposed to external and at times internal forces that impact on the day-to-day running, and the wider movement. Despite both physical and psychological damage that protest camp are open to, they continue to be a strong source of activism. In the same period that celebrated the twentieth anniversary of Twyford, and as new camps emerge in France and Malyasia, there are plans for camps around next year’s G8 meeting in the Lake District, and Occupy. As for Camp Floz, the rebuilding has begun. The communal area and information huts have risen from the ashes. The new commune area, although a little smaller, has been rebuilt at as point to organise action and continue to support Miranda who remains in her tree-sit.

[ii] http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/1623760/australian_ecoprotest_camp_destroyed_in_arson_attack.html#

[iv] See footage here courtesy of You Tube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzm1RBqCFWE

[v] Sydney Morning Herald newspaper coverage of incident, http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2008/10/22/1224351351132.html

[vi] Lester, L. (2010) Media and Environment: Conflict, Politics and the News, Cambridge : Polity

[vii] For more on Miranda and SWST activities and blog go to http://observertree.org/category/media-releases/

[viii] Foucault, M. (1986). The Care of the Self: The History of Sexuality. Vol. 3. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Random House.

[ix] Szerszynski, B. (1999). “Performing Politics: The Dramatics of Environmental Protest”. In: J. Larry, R. Ray, and A. Sayer, Culture and Economy After the Cultural Turn, London: Sage

[x] Howarth, D. (2006) Space, Subjectivity and Politics, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political April 31: pp105-134

[xi] Hairies’ – undercover cops who created false identities to infiltrate radical protest groups during the 60s, 70s and 80s.They were termed hairies” because of the way its officers dressed, looked and lived. “It was a shadowy section of the branch where people disappeared into a black hole for several years,”(Taylor, 2002:2)

[xii] http://www.fomphc.org.uk/viewpage.php?page_id=45 (accessed September 7th, 2011)

[xiii] NETCU is a national policing unit set up by ACPO to respond to the threat of domestic extremism in England and Wales. NETCU’s objective is to aid peaceful protest, and rout out “a few individuals [who] resort to criminal activity to further their cause. These individuals sometimes try to hide their illegal activities by associating themselves with otherwise peaceful campaigners.” They are overseen by the Counter Terrorism Command. For more information, see http://www.netcu.org.uk/about/about.jsp (accessed 17 October 2012).

[xiv] The Counter Terrorism Command took over terrorism-related issues from the Anti-Terrorism Squad and Special Branch. Their remit is to provide a response to “terrorist, domestic extremist and related offences, including the prevention and disruption of terrorist activity”; gather intelligence on terrorism and extremism in London, bomb disposal, work with the “British Security Service and Secret Intelligence Service” and to offer “protection of British interests overseas and the investigation of attacks against those interests”. For more information, see http://www.met.police.uk/so/counter_terrorism.htm (accessed October 2012).

[xv] Hatterstone, S.(2011).’ Mark Kennedy: Confessions of an undercover cop’, The Guardian, online at http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/mar/26/mark-kennedy-undercover-cop-environmental-activist