Ali Hugill reports from Occupy Talks Toronto for protestcamps.org

The vocabulary of occupation has recently gained a global political prominence for the Left. Those of us calling ourselves the ‘99%’, who – with varying degrees of radical fervour – broadly oppose ostentatious displays of capitalist wealth at the expense of general social welfare, have descended upon Wall Street and other urban financial districts to OCCUPY.

The vocabulary of occupation has recently gained a global political prominence for the Left. Those of us calling ourselves the ‘99%’, who – with varying degrees of radical fervour – broadly oppose ostentatious displays of capitalist wealth at the expense of general social welfare, have descended upon Wall Street and other urban financial districts to OCCUPY.

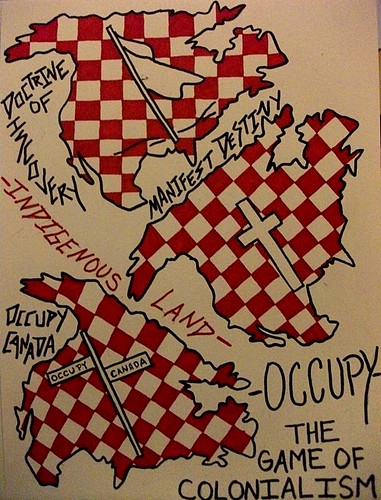

Yet opponents of the moniker ‘Occupy’ argue against it on the grounds that in North America (among other locales) we already reside in an occupied territory. Colonial occupation is ongoing on this continent and to tie a new ‘revolutionary’ movement to the logic of occupation is to efface this legacy of systemic racist violence. Some Indigenous and anarchist groups have agitated for a name change, to ‘Decolonize’ or ‘De-Occupy’. In the face of this rampant use of the term Occupy for ostensibly radical purposes, these groups have proposed an effort to interrogate the colonial logic of the movement itself: to Decolonize the 99%. This action seeks to encourage self-critique in the movement and its supporters.

The question “What does it mean to ‘Occupy already occupied lands?” was the subject of an event at Beit Zatoun Palestinian Cultural Centre in Toronto this week, investigated as part of a series of public discussions called the ‘Occupy Talks’ and organized by Occupy Toronto. Speakers at the event included: Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, writer, activist and Adjunct Professor in Indigenous Studies at Trent University; Clayton Thomas-Muller, Northern Manitoban Cree activist for Indigenous and environmental rights, and Tom B.K. Goldtooth, Executive Director of the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) based in Minnesota. The talk was moderated by Indigenous artist and academic Tannis Nielson.

Nielson briefly introduced the discussion with a call to recognize the similarities of colonial and capitalist logic and the way in which the economy has grown and continues to grow through the maintenance of racial inequality. She then turned the floor over to the first speaker, Leanne Simpson.

Simpson spoke compellingly of 400 years of resistance by Indigenous people as the longest social movement in Canada, pre-dating Canada itself. As a result, the term occupation sounds, for Indigenous people, like political and cultural genocide. In light of this, she argues that we need to reject the language and ideology of conquest and colonialism entirely. Decolonisation needs to be at the centre of the movement. Simpson’s own experience of resistance was influenced by the Indigenous women in her community, whose love, commitment and strength made survival as resistance possible. She presented the Occupy movement with a challenge: make the concerns of Indigenous women central. This, she argued, would make the movement truly radical.

Simpson spoke compellingly of 400 years of resistance by Indigenous people as the longest social movement in Canada, pre-dating Canada itself. As a result, the term occupation sounds, for Indigenous people, like political and cultural genocide. In light of this, she argues that we need to reject the language and ideology of conquest and colonialism entirely. Decolonisation needs to be at the centre of the movement. Simpson’s own experience of resistance was influenced by the Indigenous women in her community, whose love, commitment and strength made survival as resistance possible. She presented the Occupy movement with a challenge: make the concerns of Indigenous women central. This, she argued, would make the movement truly radical.

Clayton Thomas-Muller then recounted his initial reaction to the announcement that Wall Street had been occupied. He was in Raleigh, North Carolina at a meeting of what he described as “the most radical people in the country,” a group of activists representing various racialized groups from across the continent. Someone in attendance got on the mic to announce that he’d just read on twitter that Wall Street had been occupied. Everyone looked around the room and asked each other: “Who’s leading this?” None of them had heard about the plans, and they considered themselves to be well connected in various activist communities.

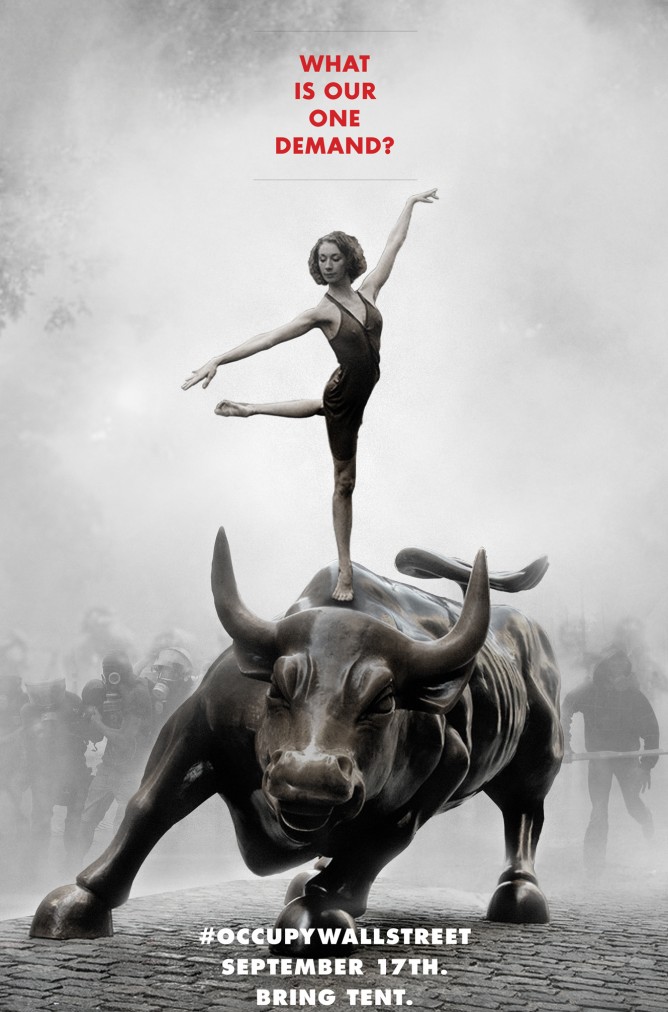

Upon making a few calls, they quickly learned the source: “Adbusters.” “Isn’t that some art magazine?,” someone asked. Footage from the occupation shortly emerged, revealing a large contingent of mostly middle class white youths. Thomas-Muller described his initial reaction as one of fear. He was afraid that the scenario could turn into one where various social movements would become alienated and dispersed. He feared that many of the participants were uneducated and unprepared, especially in terms of anti-racism training. He worried that they had already forfeited the crucial opportunity to move socially disadvantaged groups to the fore of the movement.

Upon making a few calls, they quickly learned the source: “Adbusters.” “Isn’t that some art magazine?,” someone asked. Footage from the occupation shortly emerged, revealing a large contingent of mostly middle class white youths. Thomas-Muller described his initial reaction as one of fear. He was afraid that the scenario could turn into one where various social movements would become alienated and dispersed. He feared that many of the participants were uneducated and unprepared, especially in terms of anti-racism training. He worried that they had already forfeited the crucial opportunity to move socially disadvantaged groups to the fore of the movement.

Retelling this story in Toronto, Thomas-Muller confessed that he believed his fear to have come true. He spoke about some of his encounters at different occupy sites worldwide, where he was continually met with people saying: “Stop being like that, can’t you just forget about it. Give it a chance to grow. The occupy thing: semantics, man! Semantics.” His response? “FUCK THAT! Occupy is offensive. I know that’s abrasive but I really want to get you all to understand what I’m trying to say here. The fact of the matter is that when we have convergence [of different radical political groups] we have to make sure that we aren’t creating a situation where a bunch of people are getting harmed. And if people are getting harmed then that’s a fucked up strategy and we have to let that go.” Thomas-Muller spoke about his experience at Climate Camp in the UK as an example of a positive convergence strategy.

The final speaker, Tom B.K. Goldtooth, began his talk with the question: Where do we go from here? He discussed the protocols of Indigenous peoples when dealing with visitors from different regions. “Where is our protocol for communication in this context?” he asked. He suggested that we need to reevaluate our relationship with the female creative principle of Mother Earth and acknowledge that Indigenous people are the settlers’ ‘older brothers and older sisters’ and should be respected accordingly.

“As you occupy Wall Street” he said, “reflect on the recent demands from the American Indian Movement of Denver, Colorado”: to repeal the papal bull Inter Caetera (1493) or ‘Doctrine of Christian Discovery’ and to support and endorse the right of Indigenous peoples to self-determination as sovereign nations. He praised the impetus behind the Occupy movement but emphasized the necessity for inclusion of Indigenous demands.

Goldtooth insisted that a movement based upon principle was needed, in light of which certain crucial questions would emerge. Most importantly at this point: what is a process for outreach and inclusion of indigenous people? Is this merely a moment or is it a movement? The tactical frame of the movement is the 99% – but who, he asks, is represented by that number? The movement is popular and diverse and, as such, Goldtooth insists that we must have clear protocols for dialogue, which would encompass this diversity. This requires combatting internalized oppression as well, and acknowledging that the system we are fighting is adept at instilling a sense of disempowerment, paralysis and isolation.

Goldtooth insisted that a movement based upon principle was needed, in light of which certain crucial questions would emerge. Most importantly at this point: what is a process for outreach and inclusion of indigenous people? Is this merely a moment or is it a movement? The tactical frame of the movement is the 99% – but who, he asks, is represented by that number? The movement is popular and diverse and, as such, Goldtooth insists that we must have clear protocols for dialogue, which would encompass this diversity. This requires combatting internalized oppression as well, and acknowledging that the system we are fighting is adept at instilling a sense of disempowerment, paralysis and isolation.

Goldtooth’s talk concluded the session on a hopeful note: he believed that despite initial setbacks, the possibility remained to assert Indigenous rights from within what is presently known as the ‘Occupy’ movement.

3 Responses to OCCUPY TALKS TORONTO: Indigenous Perspectives on the Occupy Movement