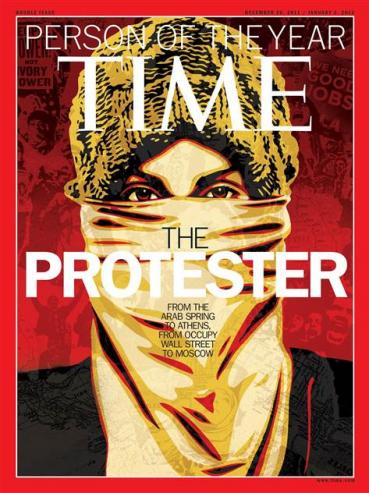

The ethnically ambiguous, stylised protester staring at us off of TIME Magazine’s cover is certainly seductive. Interpellating all those who’ve taken to the streets, her presence rewards us like a prideful parent patting their child on the back for an A grade assignment. We can hang her picture on the wall in recognition of our stellar performance.

Yet while this TIME feature certainly prompts some celebration, it also serves as a warning sign. In a speech at Occupy Wall Street’s Zuccotti Park in early October, social critic Slavoj Zizek warned campers not to “fall in love with themselves.” Back in October the swift movement of Occupy camps igniting across the US and then abroad, made change feel immanent and resistance immensely powerful. Accounting for this success, Zizek told campers to go forward with caution:

“Beware not only of the enemies, but also of false friends who are already working to dilute this process. In the same way you get coffee without caffeine, beer without alcohol, ice cream without fat, they will try to make this into a harmless, moral protest. A decaffienated process.”

As ‘The Protester’ image proliferates across facebook pages with profile pictures changed to adopt its symbolic form, it is important to ask: Why has TIME magazine sent out this friend request? In its attempt to befriend these movements, what stories of the present and memories of the past does TIME also ask us to accept?

From its very first paragraph this cover story by Kurt Anderson frames the history of protest as a struggle for liberal democracy. Struggles in the Segregated US and Apartheid South Africa are framed around civil liberties, with no mention of class, poverty or the economic exploitation embedded in violent and repressive regimes of racial apartheid. Entirely absent or largely rewritten are protests against the capitalist system, from factory occupations of the 1920s to the mass global uprisings around G20, WTO and other international summits of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

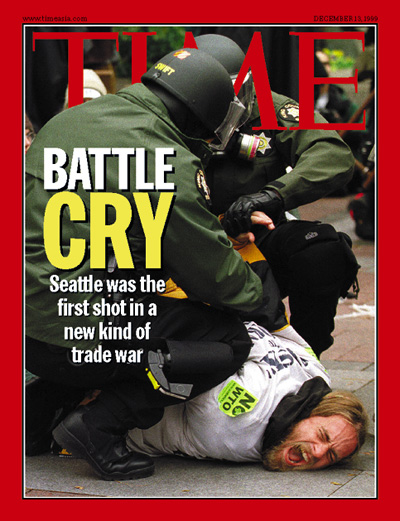

These omissions and revisions of socio-economic struggle make the present moment seem as if it has arisen spontaneously, rather than built up over decades of protest against neoliberal policies and agendas that deregulated corporate practices, destroyed unions, and replaced social good with a belief in the benevolence of private capital. In a prime example, Anderson writes off The Battle for Seattle as “ineffectual and irrelevant,” arguing later in the article that until 2011, globalization “referred to a fluid worldwide economy managed by important people.” According to Anderson it wasn’t until this year that “do-it-yourself democractic politics became globalized.”

While the mainstream media often have memory lapses, it is somewhat surprising that TIME magazine has forgotten its own coverage of the debates around economic globalization. For example in their 1999 issue covering the now “irrelevant” Battle of Seattle in which TIME journalist Tony Karon wrote that the protests “issued a profound challenge to politics as usual in the Clinton era” and that “the aftershocks of the battle for its streets may reverberate in American politics.” Likewise, a 2006 a TIME article questioned if there was ‘A Backlash Against Globalisation?’ reporting that “a quick look around the planet might lead to the impression that globalization is in crisis.”

Hand-in-hand with the global restructuring of trade and commerce, came the further individualisatoin or atomisation of everyday life. The dissolution of unions and cuts to public services combined with increasing rhetoric around the pursuit of individual prosperity became the driving economic force in global capitalism. And just as success was rated on individual achievement, so too was economic failure. Joblessness, bankrupty and foreclosures were blamed on individuals’ poor financing, greed and laziness.

One of the great successes of the M15 and Occupy movement so far has been their work to expose myths around unemployment, the mortgage crimes of banks and credit-rating institutions, and injustices around housing–efforts that all deserve praise. But these are not the collective achievements celebrated by TIME magazine. Instead, like Zuckerberg in 2010, this winter ‘The Protester’ is crowned employee of the year.

Not only does TIME offer praise for turning unwaged, underwaged and precarious labour time into productivity in the protest camps, something even more sinister is happening. When protest campers give up their ‘free time’ to build their protest, they create wealth. This wealth–the ideas and actions of people in a movement–is measured up by capital. In this way free work, via engagement for a better world, becomes ‘productive’ in a capitalist sense. The wealth the protester produces can be turned into monetary value. With their celebration, TIME is commodifying ‘The Protester’ into a spectacle for cultural consumption. Will TIME be sending pay checks to the people on the streets that helped sell magazine copies this week? It’s unlikely. (In fact, these movements might well consider billing TIME for the commodification of their protest work!)

artist unknown

Yes, the Occupy movement is swarming with creativity, ingenuity and problem-solving skills, but the Occupiers’ real protest lies in turning these efforts toward a collective project of refusal. One of the things many in the movement know they do not want is an economy that only sustains output which generates profit. The individualisation and monetization of innovation corresponds to the greed and corruption proffered by a neoliberal, capitalist system in ways that demand deeper reflection.

In addition, this tidy picture of the hard-working and well-meaning protester makes only slight reference to protesters who “might be beaten or shot, not just pepper-sprayed or flex-cuffed.” This framing censors the realities of police and military violence faced by protesters as clearly outlined in Nina Power’s article for The Guardian. These kinds of cross-cultural comparisons about the severity of violence also work to legitimise non-lethal force and cover-up links between nation’s deployment of violent repression as they share strategies (i.e. coordinated camp evictions) and technologies (i.e. teargas) across borders. Likewise, far from a hip accessory, wearing a mask in protest to protect your nostrils from teargas and your identity from police surveillance is actually outlawed in Germany, prevented increasingly by police in Britain and currently being made illegal in Canada.

While much of TIME magazine’s praise for The Protester resonates with the potency of possibility continuing to energize these movements, perhaps it’s good to hold onto a healthy scepticism. As Zizek encourages, we might be wise to beware of false friends.

Protest Camps thanks Emma Dowling for the insightful discussion on the anti-globalization movement, entrepreneurialism and precarious labour that helped shape this post.

Pingback: Occu-Links 12/28/11 | OccupyNWA

Pingback: Occu-Links 12/28/11 | OccupyNWA

Pingback: Occu-Links 12/28/11 | Occupy News